The Greeks who participated in the Cassini spacecraft mission

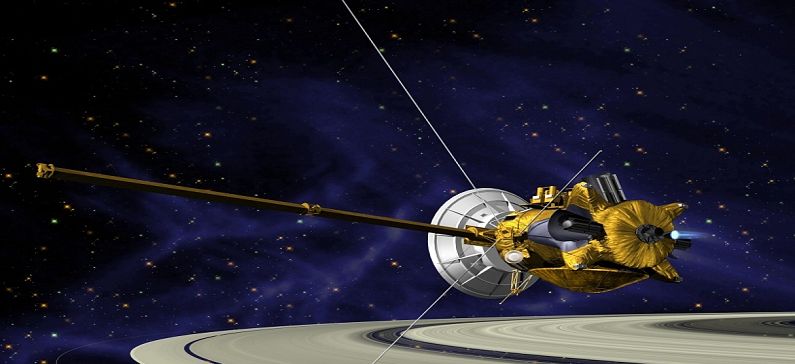

On September 15 2017, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will complete its remarkable story of exploration with an intentional plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere, ending its mission after nearly 20 years in space. Among the researchers, who have been involved in analyzing the valuable data provided by Cassini, are several Greek scientists.

The Greek scientists participated in various stages of the mission. Some of them are already in USA, where they are invited to attend the NASA’s JPL in Pasadena, California, to see the endof the Cassini mission, such as Mr Krimigis and Ms Coustenis.

Launched in 1997, Cassini arrived in orbit around Saturn in 2004 on a mission to study the giant planet, its rings, moons and magnetosphere. In April of this year, Cassini began the final phase of its mission, called its Grand Finale, a daring series of 22 weekly dives between the planet and its rings. On Sept. 15, Cassini will plunge into Saturn, sending new and unique science about the planet’s upper atmosphere to the very end. After losing contact with Earth, the spacecraft will burn up like a meteor. This is the first time a spacecraft has explored this unique region of Saturn, a dramatic caonclusion to a mission that has revealed so much about the ringed planet.

Ellines.com contacted the Greek scientists who participated and they shared with us their thoughts on the Grand Finale of the Cassini mission.

The Greeks that were involved in the mission are:

Stamatios Krimigis has been the Principal Investigator for MIMI on Cassini–Huygens.

“The Cassini instrument was designed to image the ions that are trapped in the magnetosphere of Saturn. We never thought that we would see what we’re seeing and be able to image the boundaries of the heliosphere.”

Athena Coustenis participated in European Space Agency’s (ESA) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) space missions and was heavily involved in the Cassini-Huygens mission as well as into the preparation of future space missions to Jupiter and Saturn planets.

“The Cassini expedition ends on September 15, 2017 with an astonishing “Grand Finale”. It has amazed scientists and the whole world with the outstanding discoveries about the entire Saturn system. Having flown 127 times above Titan, the largest Earth-like satellite, Cassini gathered a large amount of data in all areas. At the moment I am at the NASA JPL to witness these last days of this fantastic mission… I’ll deal with the analysis of all the data for several years ahead.

I have participated in the Cassini-Huygens mission since conceiving its creation and its development in the 1990s, so I feel sorry for the end of this wonderful adventure. In recent years (from 2004 to today), I have dealt with the analysis of the data obtained from the Cassini-Huygens mission, concerning Saturn’s system, and especially its larger satellite, Titan. As a co-investigator of four organs of this mission (2 of the Cassini spacecraft: VIMS and CIRS and 2 of the Huygens: HASI and DISR detector), I have access to a large data recovery, and I spend a lot of time analyzing the measurements concerning Titan and other Saturn’s frozen satellites, including Enceladus.

These instruments allowed us to discover:

- how Titan’s atmosphere changes with seasons lasting 7.5 years each…

- the chemical composition of the surface and the its content of methane.

- the chemistry and composition of Titan’s stratosphere and new molecules in the CIRS spectrum, making a complete model of the atmosphere including seasonal influences and other aspects of the satellite’s meteorology.

- the surface and interior of Titan and Enceladus, with an emphasis on the tectonic analysis of data that reflects possibly on a recent volcanic activity and the existence of an inner ocean of liquid water on the two satellites.

For the interpretation of all the data, concerning the nature of the atmosphere and the surface of Titan and Enceladus, I work in collaboration with many European and American colleagues.

In the future, I hope we will return to the Saturn system, as Cassini has brought us a lot of discoveries and new questions… We need to explore the satellites Titan and Enceladus with vehicles on the ground, due to the fact that the composition of the surface and the inland water oceans need confirmation and characterization. We must return to a new age to see what changes in the surface and atmosphere of Saturn and Titan. To see if the jets of Enceladus change areas and if they are still visible or if they are seasonal phenomena… To find out what the age and the composition of the rings are. We have many things to explore yet to satisfy the curiosity of the public and scientists…

Together with the relative sadness for the end of the mission, I have the pleasure of living a new mission, as long as the spacecraft in the last few days and when it sinks into the atmosphere of Saturn will give us the opportunity to get a lot of new data on the rings and the planet”.

Jean Dandouras‘ research interests include particular Saturn’s magnetosphere and its interaction with Titan, this moon with a very dense atmosphere, resembling the pre-biotic atmosphere of Earth. He is involved as co-investigator in the MIMI experiment onboard the Cassini mission to Saturn.

“My participation in the Cassini spacecraft was with the design and creation of the on-board unit that controls the operation and digitally processes the measurements of one of the Cassini instruments, the MIMI (Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument). Mr. Krimigis, from Johns Hopkins University (Maryland), was in charge for MIMI and my team at the University of Toulouse undertook the “electronic brain” of this instrument. The purpose of MIMI was to study Saturn’s magnetosphere by depicting it with a new technique, detecting the neutral atoms emitted by the magnetosphere.

Then, thanks to the MIMI measurements, I worked on the study of the interaction between Saturn’s magnetosphere and the upper atmosphere of Titan, the only satellite in our solar system that has such a dense atmosphere, and whose composition has many analogies to composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. In this way we understood the physical mechanisms in the upper atmosphere of Titan a little bit better”.

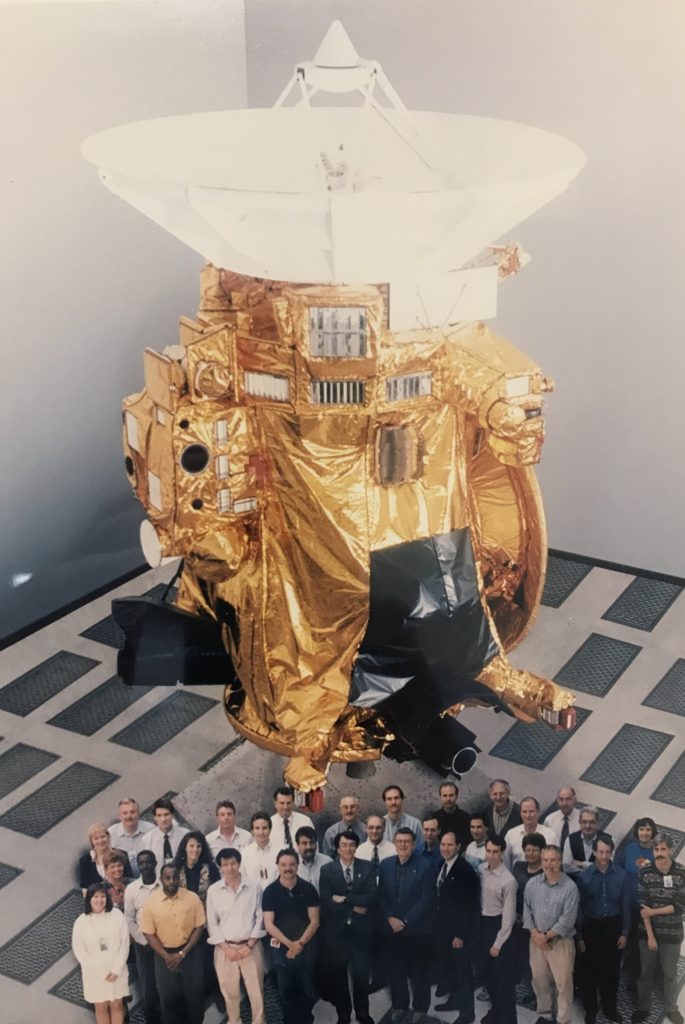

Cassini / MIMI team and the spacecraft back in 1997 (from Nikolaos Paschalidis’ archive)

Nikolaos Paschalidis is Senior Scientist and Chief Technologist for the Heliophysics Science Division of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. He held leading roles with advanced technology systems in many NASA / ESA space missions including the: Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission, JUNO, Pluto New Horizons, Van Allen Probes, IBEX, MESSENGER, IMAGE and CASSINI.

“I worked on Cassini mainly during the flight hardware development phase in the 1990s. There was a big thrust at the time to make innovative low power and small size advanced technology systems that can survive the harsh space environment reliably for a long time. I focused my efforts in design and development from scratch of a set of Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) and electronics for the MIMI particle instrument suit, led Dr Stamatios Krimigis as Principal Investigator. After a successful development and space qualification the system was integrated in the MIMI instrument and for 20 years now performed flawlessly and produced excellent measurements of particles in the Saturnian magnetosphere“.

Elias Roussos studied the data sent to Earth by the Cassini spacecraft.

“Cassini is the second largest spacecraft built to explore one of the planets of our solar system, Saturn. It was launched in 1997 from Cape Canaveral in Florida and entered orbit seven years later, in July 2004. A few months later, it released the European space device Huygens to Titan, the second largest natural satellite of the solar system and the only one surrounded by a dense atmosphere. Huygens entered Titan’s atmosphere on Jan. 14, 2005, which was studied extensively during its descent before successfully landing on the surface. The orbital Cassini continued the exploration of Saturn, its moons, and its rings until the planned end (September 15, 2017), with the 12 experiments it carries. Until this day, nearly 4,000 scientific papers have been published, many of which concern separate and unexpected discoveries, such as the observation of water jets and ice crystals in the south pole of Enceladus, one of the 62 satellites of Saturn. Today we know that these jets originate from a water ocean in the subsoil of this moon, making Enceladus one of the most attractive targets for future exploration and search for microbial life in our solar system.

I participate in the MIMI (Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument) experiment, the director of which is the Academic Dr. Stamatios Krimigis. The experiment includes three detectors meters of charged and neutral high-energy particles, which shape Saturn’s space environment, including the radiation belts the particles of the planet’s cosmic rays that coexist with some of its moons. The aim is to understand the structure of this environment, which physical mechanisms it modulates modulate it, how it changes with time, and how it interacts with the rings and satellites of the planet”.

Anezina Solomonidou‘s main interest is the interpretation of the geological features of Titan in addition to the correlation with the terrestrial geological terrain in order to have a ‘view’ of the past history and/or the future evolution of their geology. During her postdoctoral thesis she tried to answer some of the current fundamental questions arising from the Cassini-Huygens and ground-based observations. She studied more specifically the active zones i.e. regions that are subject to change over time, with a view to the finding out whether cryovolcanoes exist on Titan.

“I have been working since 2007 with the Cassini-Huygens mission, and in particular with the research of Saturn’s largest satellite system, Titan. I first came in contact with the mission during my postgraduate studies at the University College London (UCL), where my diplomatic thesis was about creating volcanic models for the Titan satellite using Cassini instrument data.

Then I elaborated my doctoral thesis with Dr. Athena Coustenis at the Observatory of Paris, in collaboration with the University of Athens and Prof. Xenophon Moussas. The subject of my doctoral thesis was the geological environments of Titan and Enceladus, having as the main research field the possibility of cryovolcanoes in these planetary bodies, always through the use of Cassini data.

From 2014, I am at the California Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which is the Cassini Mission Management Center, and I work with Dr. Charles Elachi, outgoing director of the center and chief investigator of a Cassini instrument, the radar. My main concern is the analysis of Cassini’s VIMS spectral data from which we receive information on the chemical composition of the terrestrial soils and the analysis of the radar data from which we obtain information on morphology and tectonics of the territories. The aim is, based on these facts, to create accurate models to confirm the connection of the interior of Titan and its liquid underground ocean with its surface and atmosphere, in order to decipher geology, atmosphere, and astrobiology and to get a step closer to knowledge in relation to creating and maintaining life on planetary bodies beyond the Earth.

Knowledge and information about such far-off bodies that we receive from large missions such as Cassini’s helps us to decipher and deepen our understanding of the Earth’s evolution and the creation of life on our planet since the Archaic period. The Cassini spacecraft will hit the Saturn on 15 September 2017, as its fuel is no longer sufficient to continue traveling and collecting data. This impact on the planet was decided in order to avoid the possible destruction (partial or total) of a smaller body of the Saturn system, as well as any biological contamination of that body that would probably follow. However, after the spacecraft’s “Grand Finale”, our Earth exploration of Saturn and its satellites will continue for many years using the data we have received from this highly successful mission and for many of us the most important mission in our external solar system”.

Aikaterini Radioti is a researcher at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Planetary Physics (LPAP) in the Department of Astrophysics, Geophysics and Oceanography (AGO) at the University of Liège. Thanks to an ESA PRODEX contract, she was able to go onto study Saturn’s aurorae, observed with the Cassini probe’s UVIS instrument.

“I started my research in the Jupiter Magnetosphere in 2003 when I started my PhD at the Max-Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany. Since 2006 I am at the University of Liege in Belgium (Laboratoire de Physique Atmospheric et Planétaire) and I continued my research on Jupiter and Saturn’s magnetosphere, studying the aurora on these two planets with data from the Hubble Space Telescope and Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS).

In recent years, I have been working mostly with Cassini’s UVIS images, which photograph the aurora. I am an official member of the UVIS group and have direct access to UVIS data. The study of the aurora helps us to understand Saturn’s interaction with his space environment. In particular, we study the magnetosphere particles that create the aurora and the interaction they have in Saturn’s atmosphere. We can also understand whether the magnetosphere of this enormous planet is affected by the solar wind or by internal processes. The great advantage of studying the aurora compared to other magnetospheric measurements is that by analyzing the data we have an idea of what is happening precisely on the planet’s magnetosphere at this time and not on a single part of the magnetospere, on which the spacecraft is located.

Prior to Cassini, the study of the aurora in Saturn had been limited to Hubble’s data, in which the angle and the resolution were not good enough to allow detailed studies of its structure and, by extension, the understanding of Saturn’s magnetosphere. Data from UVIS and Cassini changed the image we had until recently on Saturn’s aurora”.

Nicholas Achilleos has been a mission planner for the team who managed the magnetometer instrument onboard the Cassini spacecraft and a science co-investigator for the Cassini magnetometer team.

Panayotis Lavvas is a research scientist studying the physical and chemical processes of planetary atmospheres. His work is funded by the Centre National de la Research Scientifique (CNRS) in France, and he is based in the Groupe de Spéctrometrie Moléculaire et Atmosphérique (GSMA) of the Université de Reims Champagne Ardenne (URCA). He is a Cassini Participating Scientist with the UVIS and ISS instrument teams.

Th. Economou is an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago and a NASA Senior Planetary Scientist. He has been building instruments for interplanetary spacecraft since the mid-1960s. Currently he is associated with three robotic interplanetary missions: the Mars Exploration Rovers, the Cassini mission to Saturn, and the Rosetta mission to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Nick Sergis participated in Stamatis Krimigis’ scientific team of the Magnetic Spray Mechanism (MIMI) in early 2006, when the spacecraft arrived at Saturn. Since then he has been involved in the mission measurement analysis. Indicatively, along with St. Krimigis and Costas Dialinas, who constitute the scientific team of the Office of Space Research and Technology of the Academy of Athens, published more than 70 scientific papers over the last ten years.

Giorgos Babasides, Maria Andriopoulou, Sofia Bebesi, Dimitris Tsimpidas, Xenofon Moussas, Panagiota Preka-Papadema and Konstantinos Kyriakopoulos have also participated.

Read also:

From Chios to the endless Universe

Director of Research in the National Centre for Scientific Research of France

Studies the potential to discover life beyond our planet

Detected the elusive space wind moving around the Earth

Researcher at Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research

A modern explorer of the stars