Greek with its mathematical structure is the language of… computing and the new generation of advanced computers, because only in Greek there are no limits. (Bill Gates)

Greek and Chinese… are the only languages with a continuous living presence from the same people and in the same place for 4,000 years. All languages are considered to be crypto-Greek, with rich loans from the mother of languages, Greek. (Francisco Adrados, linguist).

The first major blow to the Greek language was the 1976 reform, with the abolition of ancient Greek and the introduction by law of the Demotic and the monotonic, which today has become atonal.

Another great blow is that the … family, the teacher and the priest have been replaced by television, which has a pernicious effect not only on the language, but also on character and morals. (Antonis Kounadis, academic)

CNN in collaboration with the computer company Apple prepared an easy Greek learning program for English and Spanish speakers in the US. The rationale behind this initiative was that Greek intensifies the rational spirit, scratches the entrepreneurial spirit and encourages citizens towards creativity.

By counting the different words in each language we see that they all have several thousand, so it is impossible to have a script that has as many letters as there are words in a language, because no one would remember so many symbols.

The same is true of the different syllables of words (e.g., a, ab, ba, bra, b, ve, u. ) that each language has.

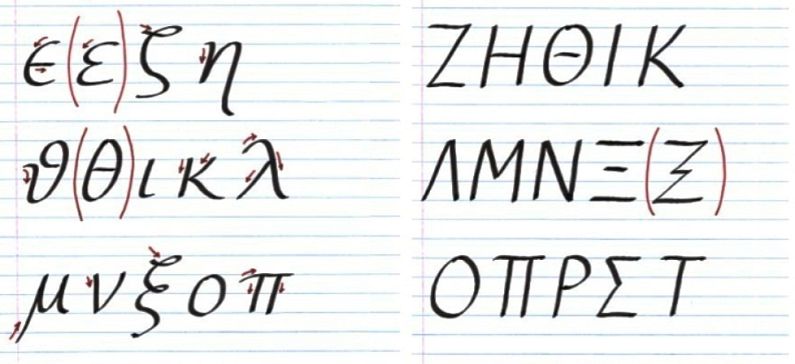

Counting also the different phonemes of words (the: a, b, c. ) that each language has, we see that these are relatively few, there are only 20, namely: a, e, o, o, th, i, k, c, h, t, d, i, p, b, f, m, n, l, r, s, z , but if we record the words only as having phonemes, we cannot distinguish the homophones, e.g.: “tihi” = walls, walls, tyche, tychee, “kali” = good & good & calls.

Therefore, it is not possible to have a script that has as many letters as the different phonemes of the words.

Before this problem, people resorted to various tricks to achieve the recording of the spoken word, the main ones being the Egyptian and Greek.

The trick invented by the ancient Greeks in order to record words phonetically was the use of as many letters as there are phonemes in the words, vowels and consonants, i.e. the letters A(a), B(b), C(c). and on the other hand some homophonous letters, i.e.: O(o) & O(o), H(h) & Y(y) & I(i) with which, according to rules, on the one hand the etymology (= the part of speech or the type etc.), thus the exact meaning of the words is indicated and on the other hand the homophones are distinguished, cf.

It is a disparity, for example, that in Greek writing it has been arranged to write the last vowel of verbs with the letters – oh, i and of declining verbs with – o,i,h, in order to distinguish the homophonic types: call & good, call & good, fig & rise, kiss & race, kiss & sex.

He similarly disregarded that in Greek writing it has been arranged to write nouns with a capital letter and common names with a small letter, to distinguish homophones: niki & Niki, agathi & Agathi.

HISTORICAL CONTINUATION

Greek is the only language in the world that has been spoken and written continuously for at least 4,000 consecutive years, as Arthur Evans distinguished three phases in the history of Minoan writing, the first of which dates from 2000 BC to 1650 BC.

One may disagree and say that Ancient and Modern Greek are different languages, but this is of course completely untrue.

Ulysses Elytis himself said “I know of no other language but one, the single Greek language. For the Greek poet to say, even today, the sky, the sea, the sun, the moon, the wind, as Sappho and Archilochus used to say, is no small thing. It is very great. We communicate every moment by talking to the roots that are there. In the Ancient Ones.”

The great teacher of the genus Adamantios Korais had said: “Whoever without the knowledge of the Ancient One attempts to study and interpret the Nean, either deceives or deceives”.

Although thousands of years have passed, all Homeric words have survived to this day. They may not have been preserved intact, but they have remained in our language through their derivatives.

We may say water instead of water, but we say hydrophore, aqueduct and dehydration. We may not use the verb skinned (see) but we use the word skinned. We may not use the word αυди (voice) but we still say stunned and appalled.

Also, today we don’t call clothes “lopopus”, but we say the word “lopodytis” which means “one who plunges (dips) his hand into your garment (lopi) to steal from you”.

Linear B is also purely Greek, a genuine ancestor of Ancient Greek. English architect Michael Ventris deciphered this script based on some findings and proved its Greekness. Until then, of course, everyone stubbornly ignored even the possibility that it was Greek…

This fact is of enormous importance as it takes the Greek several centuries further back in the depths of history. This script is certainly strange, as the symbols it uses are very different from the current alphabet.

However, the pronunciation is similar, even with Modern Greek. For example, the word “TOKOSOTA” means “Archer” (clerical). It is well known that “k” and “s” in Greek makes “ξ” and with a simple commutative property as we do in mathematics we see that this word has not changed at all for so many millennia.

Even closer to Neo-Greek, “wind”, which in Linear B is written “ANEMO”, as well as “raptis”, “desert” and “temenos” which are respectively in Linear B “RAPTE”, “EREMO”, “TEMENO”, and many other examples.

But calculating even with the conventional chronologies, which place Homer around 1,000 BC, we have the right to ask: How many millennia did our language take from the time when the cavemen of the Greek area first articulated it with monosyllabic phonemes until it reached the astonishing perfection of the Homeric epic dialect, with words like “rhododactylos”, “leucolene”, “ocymoros”, etc.?

Plutarch in his “On Socrates the Demon” informs us that Agesilaus discovered the tomb of Alcmene, the mother of Heraclius, in Aliartus, which tomb had as its dedication “a table with many wondrous letters, a table with many wondrous letters, a table with many wondrous letters, a table with many wondrous letters…” Imagine how old the writing is, since the ancient Greeks themselves describe it as “ancient”…

Of course, it is not possible for a Homer to suddenly, “out of nowhere” appear and write two literary masterpieces, it is obvious that there must have been a language (and writing) of high level from much earlier. Indeed, we know from ancient Greek literature that Homer was not the first, but the last and most famous of a long line of epic poets, whose names have survived (Creophylus, Prodicus, Arctinus, Antimachus, Kinaethon, Callimachus) and the names of their works (Foronius, Phocaius, Danaius, Ethiopis, Epigone, Oedipus, Thebes, Oedipus… ) but their works themselves have not survived.

POSSIBILITY OF CREATING NEW WORDS

The strength of the Greek language lies in its ability to form not only prefixes or suffixes, but in some cases even differentiating the root of the word (e.g. “τρέχω” and “τροχός”, although from the same family, differ slightly in the root).

The Greek language is special at creating complex words with incredible potential uses, multiplying the vocabulary.

Webster’s New International Dictionary (Webster’s New International Dictionary) states: “Latin and Greek, especially Greek, are an inexhaustible source of material for the creation of scientific terms”, while French lexicographers Jean Bouffartigue and Anne-Marie Delrieu emphasize: “Science incessantly finds new objects or concepts. It has to name them. The treasure trove of Greek roots lies before it, if it only has to draw from it. It would be very strange if it did not find the ones it needs.”

The French writer Jacques Lacarriere, dazzled before the greatness of Greek, had stated in this regard. One has only to put a pan – first – arch – pro – or any other preposition in front of a subject.

And if you combine these prefixes together, you get an endless variety of gradations. The prefixes enclose the ones in the others like a semantic scale, which rises up to the sky of words.”

In Homer’s Iliad, Thetis laments what will happen to her son by killing Hector, “Dios and disasaristothekeia she calls it”. This word itself is a fatalism, dual + aristos + ticto (=genno) and means as the Etymological Analyst analyses the Megas “that for evil I begot the aristos”.

A few years ago the Dictionnaire Des Mots Inexistants (Dictionnaire Des Mots Inexistants) was published in Switzerland, where it is proposed to replace French colloquialisms with one-word terms from Greek. E.g. androprere, biopaleste, dysparegorete, ecogeniarche, elpidophore, glossoctonie, philomatheem tachymathie, theopempte etc. about 2,000 entries with the prospect of further enrichment.

THE ARCHIBOLOGY

It is obvious that, at least as far as punctuation is concerned, languages like Greek are clearly superior to languages like English.

It is logical, after all, if you think about it, that it is much easier to establish an international language when it is easier to learn, but on the other hand, such a language cannot de facto be of such high quality.

The consequence of the above is that English cannot be as laconic as Greek is, since in order to avoid ambiguity in the meaning of a given phrase, additional words must be used. For example, the word “drink” as a stand-alone phrase does not exist in English, as it can mean “drink”, “drink”, “drink”, “drink” etc. In contrast, in Greek the phrase “drink” makes sense without having to rely on the context to understand its meaning.

Parenthesis. There is also a Dative case in Greek in addition to the other 4 cases of nominative, genitive, causative and clitic.

The dative is constantly used in our everyday speech (e.g. Based on the measurements, we conclude that…) and it is really worthy of note why it was forcibly expelled from the modern Greek language.

Even earlier, in addition to the exiled but living Dotic, there were three additional cases which were lost.

The Chinese language has the same problem, to a much more pronounced degree, of course. As the Cretan journalist A. Krassanakis tells us: “Because simple words are few, they have acquired too many meanings to meet the needs of expression, e.g.: ‘b’ = know, be, power, world, oath, let, put, love, see, care, walk, house, etc., ‘pa’ = ballet, eight, thief, steal… ‘pai’ = white, hundred, hundredth, hundredth, lose…”

Perhaps there is a slight difference in intonation, but even if there is, how is it possible to make an important text (e.g. contract) unambiguous?

THE SOVEREIGNTY

In the Greek language there are essentially no synonyms, as all words have subtle conceptual differences between them.

For example, the word “lopodytis” is used for one who plunges his hand into our clothing and steals from us, i.e. secretly, while “robber” is one who steals from us openly, in front of our eyes. Also, “leaning” and “bearing” have the same meaning. But the former is used for animate beings, while the latter is used for inanimate beings.

In Greek we have the words “chernnymi”, “mingnymi” and “φύρω” which all have the meaning of “stir”. When we mix two solids or two liquids together but without implying a new compound (e.g. oil with water), we use the word “mix” while when we mix a liquid with a solid we say “blow”. Hence the word “bloody” which we all know but don’t realize what it means.

When the Ancient Greeks were wounded in battle, the blood flowed and mixed with the dust and dirt.

The word churn means to mix two liquids and make a new one, such as wine and water. Hence the “akratos” (i.e. pure) wine that the ancients called it when it was not mixed (kekramens) with water.

Finally, the word “married” has a different meaning from the word “married”, a difference that the words themselves describe for anyone who gives them some thought.

The word “married” comes from the verb “to be married” and means to be put under the authority of the man while the man is married, i.e. to take a bride.

Knowing such subtle conceptual differences, some of the things we hear in everyday – often incorrect – speech (e.g. “X got married”) are really quite funny.

The Greek language has words for concepts that remain untranslated in other languages, such as amimila, thalpore and philotimo. It alone separates, maintaining the same radical theme, accident from accident, interest from interest.

LANGUAGE – THE TEACHER

What is truly astonishing is that the Greek language itself constantly teaches us how to write correctly. Through etymology, we can discern the proper way of writing words—even those we have never encountered before.

Take the word “pirouni” (fork), for example. For someone with basic knowledge of Ancient Greek, it is evident that it is written with “ei” rather than “i”, as it is often mistakenly spelled today. The reason is simple: “pirouni” derives from the verb “peiro” (to pierce or penetrate), precisely because we use a fork to pierce food in order to pick it up.

Similarly, the word “sungkekrimenos” (specific) cannot logically be written as “sungkekrymmenos”. It stems from the word “krimenos” (judged or decided) rather than “krymmenos” (hidden).

Thus, the existence of multiple letters for the same sound (e.g., η, ι, υ, ει, οι, etc.) should not confuse us; rather, it should assist us in writing more accurately—provided we have a basic understanding of our language.

Moreover, spelling reciprocally aids us in etymology and in tracing the historical evolution of each word.

To deepen our comprehension of Modern Greek, nothing surpasses the knowledge of Ancient Greek.

It is truly breathtaking to speak a language while simultaneously understanding the exact meaning of the words being uttered.

Unfortunately, Ancient Greek is often taught so poorly in schools that it leads students to dislike what is inherently beautiful and fascinating.

WISDOM

In language, there is the signifier (the word) and the signified (the meaning). In Greek, these two have an intrinsic relationship. Unlike other languages, the signifier in Greek is not a random arrangement of letters. In a conventional language like English, for instance, we could agree to call a car a cloud and a cloud a car. Once this agreement is made, it could stand. In Greek, however, such arbitrariness is impossible.

This is why many distinguish Greek as a “conceptual” language, as opposed to other “semiological” languages.

The renowned philosopher and mathematician Werner Heisenberg observed this unique quality, stating, “My training in Ancient Greek was the most significant intellectual exercise of my life. In this language, there is the fullest correspondence between the word and its conceptual content.”

As Antisthenes famously declared, “The beginning of wisdom is the examination of names.”

For example, the word “archon” (ruler) literally means one who possesses land (ara = land + echon = possessing). Even today, owning land or property remains crucial.

The word “voithos” (helper) combines “voe” (call) and “theo” (run), meaning one who rushes to a call for help.

The word “astir” (star) is derived from “a” (not) and “stir” (standing still), indicating that a star does not remain stationary but moves.

The term “phthonos” (envy) comes from the verb “phthino” (to diminish). Indeed, envy erodes and destroys us, gradually reducing us as individuals—even impacting our health. Conversely, the term “afthono” (abundant) denotes something so plentiful that it does not diminish.

The word “oraio” (beautiful) comes from “ora” (time). For something to be truly beautiful, it must arrive at the right time. A fruit is not beautiful when unripe or rotten, and a beautiful woman is neither a child nor an elderly person. Even the finest meal is not enjoyable when one is full, as it cannot be appreciated.

The word “eleftheria” (freedom), as explained in the Etymologikon Mega, derives from “elefthin opou era” (to go where one loves). Thus, according to the word itself, freedom is the ability to go where your heart desires—a profound interpretation indeed.

The term “agalma” (statue) comes from “agallomai” (to rejoice), as gazing upon a beautiful ancient Greek statue fills our soul with joy, leading to “agalliasi” (exaltation). Delving deeper, this term comprises “agallomai” and “iasi” (healing).

To summarize, when we behold something beautiful, our soul rejoices and heals.

Indeed, we all know that our mental state is intrinsically linked to our physical health.

MUSICALITY

In antiquity, the Greek voice was called “audi”. This term is not random; it derives from the verb “ado” (to sing).

As the esteemed poet Nikiforos Vrettakos wrote:

“When I depart from this light, I will ascend like a murmuring stream. If I meet angels in the azure corridors, I will speak to them in Greek, for they do not know other languages. They converse among themselves with music.”

The French author Jacques Lacarrière, during his travels in Greece, described hearing locals speak in a language that sounded harmonious yet incomprehensible to him, remarking on its unique musicality.

The Greek language resonates not only as a tool of communication but as a profound expression of human thought, creativity, and emotion—a testament to the rich cultural and intellectual heritage it carries.