Ο αρχαιότερος υπολογιστής στον κόσμο

Computer or astrolabe, the mechanism that discovered in the famous shipwreck of Antikythera has fascinated many historians of science and technology.

On May 17, 1902, the former Minister of Education of Greece, Spyridon Stais, and the Ephorate of Antiquities, Gavril Byzantinos, were at the National Archaeological Museum and examined some amorphous masses of metal recovered last year from the famous Shipwreck of Antikythera.

They were the first to observe a toothed wheel, which also brought some eroded inscriptions in astronomical terms. From that moment on, the effort to identify the objects started, an effort that continues, even though it would make us thoroughly review everything we knew about the science and technology of ancient Greeks.

Its discovery is due to the sponge-divers from Symi, who, in 1900, retreated treasures, statues and other objects from 40 to 64 meters depth in the sea. Among them was the famous Antikythera Mechanism, which was found in the open of Antikythera and between Kythira and Crete. Based on the form of the Greek inscriptions it carries, it dates back to 150 BC and 100 BC, long before the date of the shipwreck, which may have happened between 87 BC and 63 BC. It could have been built up to half a century before the wreck.

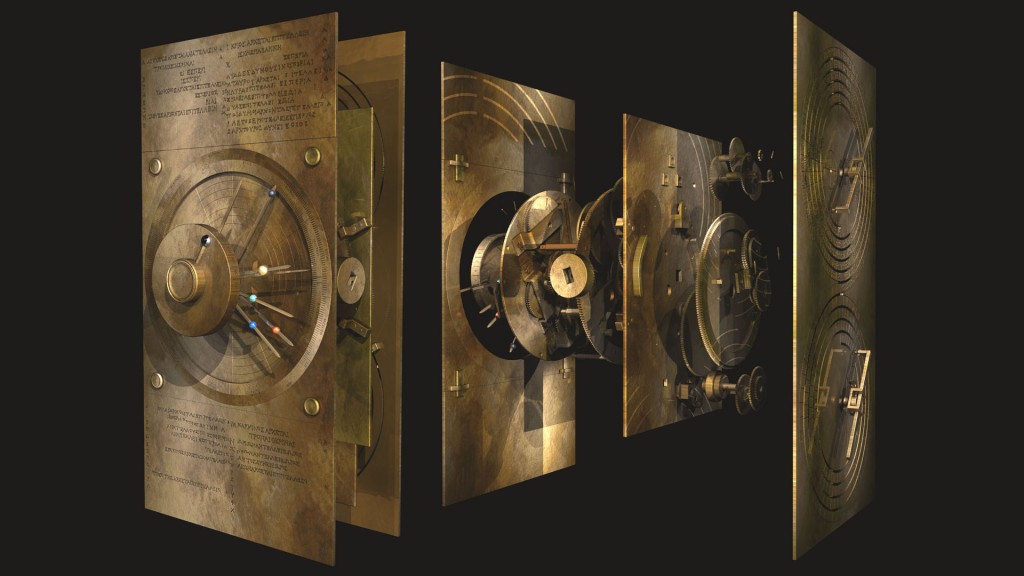

The mechanism was a wooden box, no larger than a thick dictionary (34 x 18 x 9 cm), which contained a complex gear system. Only little traces have been imprinted on the wood, while, after 2000 years in the water, the gears have been transformed into undefined masses of oxidized metal.

As a work of art, it is unsurpassed in design elegance and technical excellence, but as a work of engineering, it is even more amazing. In order to accommodate all the functions of the mechanism in such a small box, ingenious design and inconspicuous precision were needed, especially if we keep in mind the technical means of the times.

The results of many years of research confirm that the mechanism carries 30 gears that rotate around 10 axes. The operation of the mechanism resulted in at least 5 dials, with one or more indicators for each. With the help of the tomograph, several of the inscriptions on the plates and on the rotating discs containing astronomical and mechanical terms have been read and have been described by experts as a kind of manual for the instrument. This mechanism showed, in the prevailing contemporary view, the position of the sun and the moon, as well as the phases of the moon. It could show the sun and moon exiles based on Sarah’s Babylonian cycle. Its dials also depicted at least two diaries, a Greek based on the Metonic circle and an Egyptian, which was also the common “scientific” calendar of the Hellenistic era.

The Antikythera Mechanism was a machine designed to predict celestial phenomena, according to the sophisticated astronomical theories of its time, the only witness to the lost history of brilliant engineering, an idea of pure genius, one of the great wonders of the ancient world.

How It Worked

The mechanism is not made to measure hours but years and astronomical circles that last for decades. It can also foresee eclipses and represent the movements of the celestial bodies. The mechanism is a combination of an astronomical computer and a planetarium, and used to study or predict celestial phenomena and, perhaps, to set up calendars. At a time when each region had its own timing system, the latter would be most likely to be necessary.

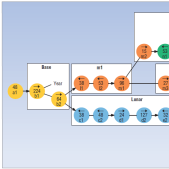

The Antikythera Mechanism, although constructed about 2000 years ago, is quite complex in its structure. The diagram (photo) developed by Professor Diomidis Spinellis presents the 30 gears that have been found in the Mechanism. Each sprocket counts the number of its teeth and the direction of rotation. An arrow shows the transmission of the gear from one to the other, while the compound gears (moving as one body) are connected by a single line.

It is obvious that the mechanism is neither an electrical nor an electronic device. The energy for its movement came from the user, who was rotating a lever or handle, which transmitted the movement through a frontal gear.

By combining gears with a different number of teeth (and different proportions) the mechanism could “multiply” and “divide” different sizes. It presents many similarities with the first mechanical computers of the 18th century, such as Pascal’s Calculator, or mechanical firing systems of which were in use in 20th the century.

The reconstruction efforts

A partial reconstruction of the facility conducted by Australian computer scientist Allan George Bromley (Allan George Bromley, 1947-2002), the University of Sydney and Sydney watchmaker Frank Percival (Frank Percival). This research has prompted Bromley to reconsider X-ray analysis of Pryce. Bromley, with the help of British Michael Wright, also produced new and more accurate x-ray imaging of the mechanism studied by a student, Bernard Gardner, in 1993.

Later, a British engineer planner John Gleave built a functional copy of the mechanism. According to his reconstruction, reading the front wheel indicates the annual course of the Sun and Moon through the Zodiac Circle during the Egyptian calendar.

The range of the 21st Century

The Antikythera Mechanism even today is a matter of thought to the scientific community. In 2014, the Greek physicist Markos Skoulatos completed his own exact operating model after two years of research. This copy of the Antikythera Mechanism fully respects the dimensions and known functions of the original. It incorporates all the latest research, such as the moon-slit mechanism, the indication of the Olympic Games and the accurate readings of the ancient inscriptions.

The study program of the Antikythera Mechanism (University of Athens, Xenophon Museum, Yannis Bitsakis, University of Thessaloniki, Yannis Siradakis, University of Cardiff, Mike Edmunds, Tony Freeth) conducted studies and an international conference in Athens on 30 November 2006 and 1 December announced the results of the most recent comprehensive investigations. Historians of mechanisms and ancient Greek astronomy and technology [X-tek, HP] also participated. At the same time, the results of the first phase of the research were published in the prestigious journal Nature.

Today, fragments of the original are kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. In the copper collection, the three largest fragments are in a showcase.