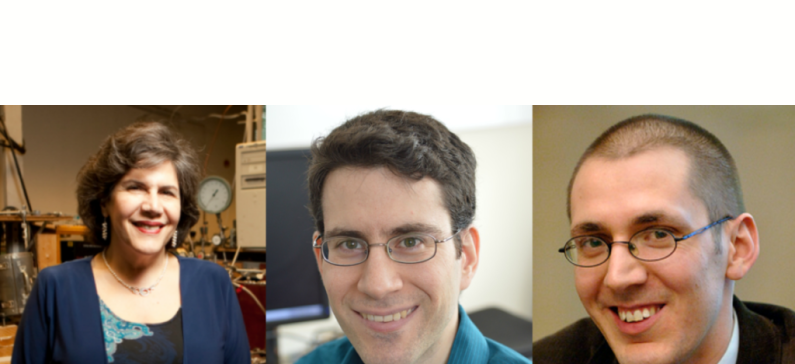

Three Greek researchers behind new innovative catalyst

Methane in shale gas can be turned into hydrocarbon fuels using an innovative platinum and copper alloy catalyst, according to new research led by UCL (University College London) and Tufts University.

Platinum or nickel are known to break the carbon-hydrogen bonds in methane found in shale gas to make hydrocarbon fuels and other useful chemicals. However, this process causes ‘coking’ – the metal becomes coated with a carbon layer rendering it ineffective by blocking reactions from happening at the surface.

The new alloy catalyst is resistant to coking, so it retains its activity and requires less energy to break the bonds than other materials. Currently, methane reforming processes are extremely energy intense, requiring temperatures of about 900 degrees Celsius. This new material could lower this to 400 degrees Celsius, saving energy.

The study, published today in Nature Chemistry, demonstrates the benefits of the new highly diluted alloy of platinum in copper – a single atom alloy – in making useful chemicals from small hydrocarbons.

A combination of surface science and catalysis experiments and powerful computing techniques were used to investigate the performance of the alloy. These showed that the platinum breaks the carbon-hydrogen bonds, and the copper helps couple hydrocarbon molecules of different sizes, paving the way towards conversion to fuels.

Study co-lead author, Professor Michail Stamatakis (UCL Chemical Engineering), said: “We used supercomputers to model how the reaction happens – the breaking and making of bonds in small molecules on the catalytic alloy surface, and also to predict its performance at large scales. For this, we needed access to hundreds of processors to simulate thousands of reaction events.”

While UCL researchers traced the reaction using computers, Tufts chemists and chemical engineers ran surface science and micro-reactor experiments to demonstrate the viability of the new catalyst – atoms of platinum dispersed in a copper surface – in a practical setting. They found the single atom alloy was very stable and only required a tiny amount of platinum to work.

Together, the team shows that less energy is needed for the alloy to help break the bonds between carbon and hydrogen atoms in methane and butane, and that the alloy is resistant to coking, opening up new applications for the material.

The study’s co-lead author, Distinguished Professor Maria Flytzani-Stephanopoulos of the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering in Tufts University’s School of Engineering, said: “While model catalysts in surface science experiments are essential to follow the structure and reactivity at the atomic scale, it is exciting to extend this knowledge to realistic nanoparticle catalysts of similar compositions and test them under practical conditions, aimed at developing the catalyst for the next step – industrial application.”

The team now plans on developing further catalysts that are similarly resistant to the coking that plagues metals traditionally used in this and other chemical processes.

The third Greek participating in the research team is Angelos Michaelides from UCL.

The research involved scientists from Tufts and UCL and used computing resources from UCL and the Argonne National Laboratory. It was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, European Research Council and the Royal Society.