Greek researcher led authorities to have ancient vase seized from Met Museum

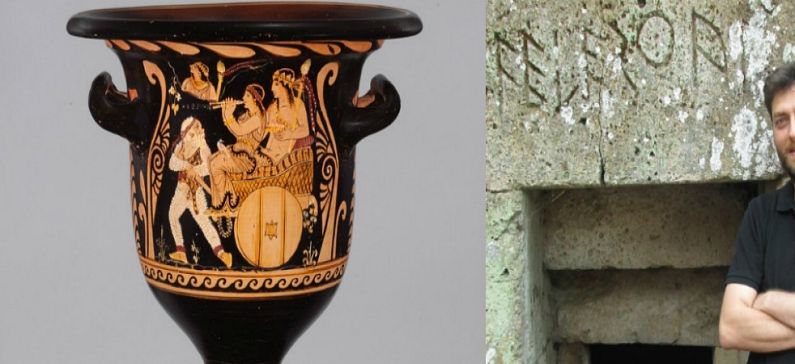

A 2,300-year-old, vividly painted vase that depicts Dionysus, god of the grape harvest, riding in a cart pulled by a satyr, which was for decades proudly displayed in the Greco-Roman galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was seized by the authorities thanks to the forensic archaeologist and Research Assistant in the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at the University of Glasgow, Christos Tsirogiannis.

Today it sits in an evidence room at the district attorney’s office in Manhattan after prosecutors quietly seized the antiquity last week based on evidence that it had been looted by tomb raiders in Italy in the 1970s. Investigators issued a warrant to the Met on July 24 after reviewing photos and other evidence sent to them in May by a forensic archaeologist in Europe who has been tracking looted artifacts for more than a decade. The museum said that it hand-delivered the object to prosecutors the next day and anticipates that the vase, used in antiquity for mixing water and wine, will ultimately return to Italy.

“The museum has worked diligently to ensure a just resolution of this matter,” Kenneth Weine, a museum spokesman, said in a statement.

The case closely echoes the removal of another terra-cotta wine vessel, the Euphronios Krater, from the museum in 2008 after evidence surfaced that it had been illegally excavated from an ancient burial ground in Italy. Met officials said they believe, as do law enforcement officials, that both vessels went through the hands of Giacomo Medici, a 79-year-old Italian art dealer who was arrested in 1997 and convicted in 2004 of conspiracy to traffic in antiquities.

Mr. Medici, reached in Italy, denied any role in connection with the recently seized vase, which the Met bought at auction at Sotheby’s in 1989 for $90,000. An official for the auction house declined to identify the consignor, citing privacy concerns, but said Sotheby’s had no knowledge of any issues with its provenance when it handled the sale.

Experts date the vase, which is also known as a bell krater, to 360 B.C. and attribute it to the Greek artist Python, considered one of the two greatest vase painters of his day.

While its significance does not rise to the level of the far larger Euphronios Krater, which the Met sent back to Italy after a 30-year dispute, the newly confiscated vessel is a remarkably intact survivor of an age when the Greeks colonized Paestum, a Mediterranean city in the Campania region south of Rome, and created temples and artworks of legendary beauty.

The forensic archaeologist who tracked the Python vase, Christos Tsirogiannis, a lecturer with the Association for Research Into Crimes Against Art, published his suspicions about the antiquity in The Journal of Art Crime in 2014 and said he sent his evidence to the Met then as well.

But Dr. Tsirogiannis said in an interview that he never heard back from the museum and, more recently, grew frustrated that no action appeared to have been taken. So last spring he sent his evidence to a Manhattan prosecutor, Matthew Bogdanos, who specializes in art crime. That evidence included Polaroid photos shot between 1972 and 1995 that he said were seized from Mr. Medici’s storehouses in 1995 and that showed the same Python vase still encrusted with dirt.

“When I sent American police the information, they immediately told me that this was ‘a great case,’ ” Dr. Tsirogiannis said. “It was abundantly clear that this rare object had been stolen.”

Dr. Tsirogiannis said his evidence suggested that the item was disinterred from a grave site in southern Italy by looters and ended up in the possession of Mr. Medici, who was convicted in a Rome court of conspiring to traffic in other ancient treasures, many of which found homes in museums around the world.

Mr. Medici said on Monday in a telephone interview that he had no recollection of having handled the vase in question. “Absolutely not,” he said. He said he had been released from house arrest last year after serving half of an eight-year sentence that was shortened by time off for good behavior and a two-year amnesty provision granted to all Italian prisoners.

“I am a free man,” Mr. Medici said. “I went on trial, it lasted years, I was convicted for some of the objects” that Italian prosecutors believed had been looted, “and now I have nothing more to do with the justice system. The story is finished.”

The Met, for its part, disputed the suggestion that it had ignored warnings about the vase. Officials said the museum had noticed Dr. Tsirogiannis’s published research in 2014 and, indeed, had been troubled by the reappearance of Mr. Medici’s name in connection with an artifact. They said they reached out informally to the Italian authorities then, but received no response. The museum said that in December 2016 it sent the Italian Culture Ministry a formal request to resolve the case. The Met said it was awaiting guidance from the Italians when Manhattan prosecutors alerted it in June to their own concerns.

The museum removed the vase at that point from its place in the Greco-Roman galleries and began a conversation with prosecutors that ended with the confiscation last week.

A spokeswoman for District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr. declined to comment, but provided a copy of the search warrant presented to the museum.

Dr. Tsirogiannis was also instrumental this year in the return of a marble sarcophagus fragment to Greece and a $250,000 amphora to Italy. Those items were seized from an art gallery in Manhattan.

The latest case comes as more and more museums are being pressed to scour their collections for items trafficked by known antiquities smugglers whose goods originated in Italy, Greece, Turkey, Cambodia, India, Egypt and other nations long plagued by looting.

In researching the Python vessel, Dr. Tsirogiannis said that he drew on his access to those files and photos, granted to him by the Greek and Italian governments. For example, he said he compared a Medici Polaroid showing the Python vessel still encrusted with dirt with an image of a similar item in a 1989 Sotheby’s sales catalog and to an image of a vase that the Met had posted online. He found all three to be identical.

Read also:

Christos Tsirogiannis: Hunter of stolen antiquities

New success for the Greek hunter of stolen antiquities

Matthew Bogdanos: Stolen historical treasures hunter

4 potentially-tainted objects identified by the Greek hunter of stolen antiquities