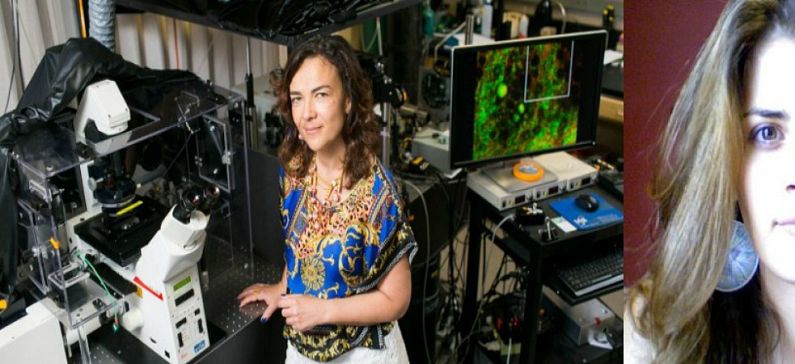

2 Greek researchers behind the new techique for skin cancer diagnosis

A noninvasive microscopy technique that exploits NADH fluorescence enables researchers to observe how mitochondria alter their shape and arrangement in human tissue. This new technique was discovered by 2 Greek researchers. Patients could one day get their skin examined under a special microscope and, in just a few minutes, know whether they have cancer, according to a new study.

Irene Georgakoudi and Dimitra Pouli are the Greek researchers behind this technique.

“The technique involves a high-resolution microscope that allows doctors to see the patient’s mitochondria — the powerhouses of the cell, which often form beautiful networks inside cells,” said the study’s lead investigator, Irene Georgakoudi, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts.

The study was published online in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Because cancer disrupts this “beautiful network,” and leads the mitochondria to become unorganized, doctors peering into the mitochondria could potentially diagnose skin cancer and other disorders based on what they see, Georgakoudi said.

Currently, doctors take biopsies of the skin to diagnose cancer, meaning they cut off a small piece of suspicious skin and send it to a laboratory, where experts inject it with dyes and then inspect it under a microscope for abnormal cells. One downside of this method is that the cut made during a biopsy can get infected or leave scars on patients.

The idea for the new technique arose about 10 years ago, when researchers realized they could look at skin tissue without having to take a biopsy. The new technique requires a type of high-resolution microscope known as a multiphoton microscope, which uses photons (particles of light) that allow researchers to see a molecule called NADH, or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. NADH is naturally present in most cells, and it glows when it’s put under light of a specific wavelength.

“When NADH is in the mitochondria, it gives off a strong signal” that helps researchers detect it, Georgakoudi said. She added that because of NADH’s unique properties, researchers don’t have to inject the patient with dyes that would highlight the mitochondria.

To test the technique, Georgakoudi and her colleagues used the microscope to take images of 10 people with skin cancer — ranging from the dangerous cancer melanoma to the less dangerous types such as basal cell carcinoma — and four with healthy skin. In all, they analyzed data from 17 diseased locations and 12 healthy tissue locations, she said.

The imaging “lasted on the order of a minute, and didn’t cause any pain or discomfort to the patient,” Georgakoudi said. “We analyzed the images, in an automated way that requires only a couple of additional minutes, to characterize the manner in which mitochondria organize.”

The researchers found that healthy mitochondria organize in different ways in different cell layers, which is no surprise, given that “cells in these different layers have different functions,” Georgakoudi said. “In the melanoma and the basal cell carcinoma lesions, these distinct variations in the organization of the mitochondria as a function of depth from the surface were more or less eliminated.” To verify the diagnoses that the researchers made using the new technique, they had a pathologist conduct a traditional biopsy on the same tissue samples, Georgakoudi added.

The new technique isn’t available for patients yet, but if it works successfully in large studies, patients could be checked for cancer in just a few minutes without having to undergo a biopsy, she said.

Moreover, although the equipment is expensive now, it’s expected that the cost of these imaging systems will decrease significantly in the next couple of years, she said.

Read also:

The biophysicist who tries to make cancer detection a lot easier