Greek researcher’s new method is making injectable medicine safer

Researchers from the University at Buffalo, among them a Greek scientist, remove excess additives from drugs, which could reduce the odds of serious allergic reactions and other side effects.

It is a promising new drug-making technique designed to reduce serious allergic reactions and other side effects from anti-cancer medicine, testosterone and other drugs that are administered with a needle.

Developed by University at Buffalo researchers, the breakthrough removes potentially harmful additives, primarily soapy substances known as surfactants, from common injectable drugs. Jonathan F. Lovell, a biomedical engineer at UB is the study’s corresponding author and Paschalis Alexandridis an Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering had a significant contribution.

“We’re excited because this process can be scaled up, which could make existing injectable drugs safer and more effective for millions of people suffering from serious diseases and ailments,” says Jonathan F. Lovell.

The work will be described in a study, “Therapeutic Surfactant-Stripped Frozen Micelles,” that will be published on May 19, 2016 in the journal Nature Communications. The paper and all information in this press release are embargoed until May 19, 2016 at 5 a.m. U.S. Eastern Daylight Time.

Pharmaceutical companies use surfactants to dissolve medicine into a liquid solution, a process that makes medicine suitable for injection. While effective, the process is seldom efficient. Solutions loaded with surfactant and other nonessential ingredients can carry the risk of causing anaphylactic shock, blood clotting, hemolysis and other side effects.

Researchers have tried to address this problem in two ways, each with varying degrees of success.

Some have taken the so-called “top down” approach, in which they shrink drug particles to nanoscale sizes to eliminate excess additives. While promising, the method doesn’t work well in injectable medicine because the drug particles are still too large to safely inject.

Other researchers work from the “bottom up” using nanotechnology to build new drugs from scratch. This may yield tremendous results; however, developing new drug formulations takes years, and drugs are coupled with new additives that create new side effects.

The technique under development at UB differs because it improves existing injectable drug-making methods by taking the unusual step of stripping away all of the excess surfactant.

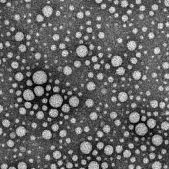

In laboratory experiments, researchers dissolved 12 drugs — cabazitaxel (anti-cancer), testosterone, cyclosporine (an immunosuppressant used during organ transplants) and others — one at a time into a surfactant called Pluronic. Then, by lowering the solution’s temperature to 4 degrees Celsius (most drugs are made at room temperature), they were able to remove the excess Pluronic via a membrane.

The end result are drugs that contain 100 to 1,000 times less excess additives.

“For the drugs we looked at, this is as close as anyone has gotten to introducing pure, injectable medicine into the body,” says Lovell, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering in UB’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “Essentially, it’s a new way to package drugs.”

The findings are significant, he says, because they show that many injectable drug formulations may be improved through an easy-to-adopt process. Future experiments are planned to further refine the method, he says.

Paschalis Alexandridis studied chemical engineering at the National Technical University of Athens, Greece, and obtained his PhD in 1994 from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Following postdoctoral research in polymer physical chemistry at Lund University, Sweden, he joined the University at Buffalo (UB), The State University of New York (SUNY), where he is currently a UB Distinguished Professor in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and Acting Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Education in the School of Engineering

and Applied Sciences.

His research focuses on elucidating the interconnection between molecular interactions, organized molecular assemblies, and their properties and function. Ongoing research addresses structuring of materials via self-assembly and directed

assembly, tailoring of macromolecular conformation with solvents, block copolymer phase behavior, polymer-nanoparticle composites, novel electrolytes, and nanomaterials synthesis. The capabilities developed by Alexandridis and his coworkers on conferring structure at the nano- and microscale find applications in the health, environment, and energy fields. He has coauthored over 125 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, has edited 2 books, and is coinventor of 10 patents on pharmaceutical formulations, superabsorbent polymers, and metallic and

semiconductor nanomaterials.

Alexandridis has received numerous recognitions for his research and teaching, including the SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship and Creative Activity (2011), American Chemical Society Jacob F. Schoellkopf Medal (2010), SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching (2006), Bodossaki Foundation Academic Prize in Applied Science (2005), Sigma Xi Young Investigator Award (2002), and National Science Foundation CAREER Award (1999). He has served as guest researcher at the Fritz-Haber Institute of the Max-Planck Society, and at the Tokyo University of Science, and was named Honorary Adjunct Professor at the Beijing University of Chemical Technology in 2011.

Read more about Paschalis Alexandridis

MARIAM CHIKANDA

-06/12/2016 3:09 pm

The rich people should assist the orphans and widows so that God will uplift, guide them in their doings and they will be Blessed. People like Costa Makris, George Koukis, Kerry Harmanis and many others. Try to assist since you are the eyes of the World. God Bless you all. Thanks.