Greek detects Jupiter-like storm on small, cool star

Astronomers, led by a Greek researcher, have discovered what appears to be a tiny star with a giant, cloudy storm, using data from NASA’s Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes. The dark storm is akin to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot: a persistent, raging storm larger than Earth.

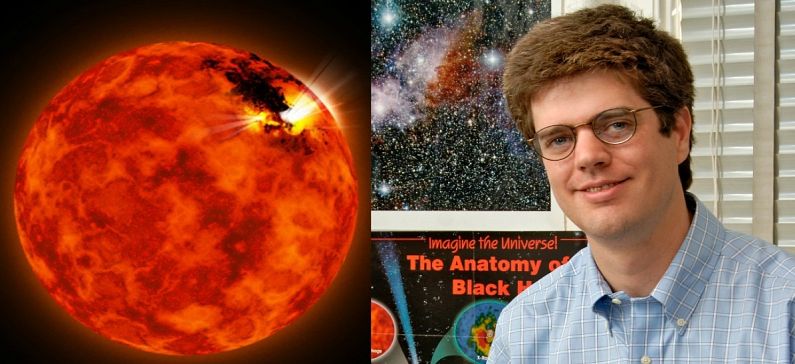

“The star is the size of Jupiter, and its storm is the size of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. We know this newfound storm has lasted at least two years, and probably longer.” said John Gizis of the University of Delaware, Newark.

Gizis is the lead author of a new study appearing in The Astrophysical Journal.

While planets have been known to have cloudy storms, this is the best evidence yet for a star that has one. The star, referred to as W1906+40, belongs to a thermally cool class of objects called L-dwarfs. Some L-dwarfs are considered stars because they fuse atoms and generate light, as our Sun does, while others, called brown dwarfs, are known as “failed stars” for their lack of atomic fusion.

The L-dwarf in the study, W1906+40, is thought to be a star based on estimates of its age (the older the L-dwarf, the more likely it is a star). Its temperature is about 3,500 °F (2,200 K). That may sound scorching hot, but as far as stars go, it is relatively cool. Cool enough, in fact, for clouds to form in its atmosphere.

“The L-dwarf’s clouds are made of tiny minerals,” said Gizis.

Spitzer has observed other cloudy brown dwarfs before, finding evidence for short-lived storms lasting hours and perhaps days.

In the new study, the astronomers were able to study changes in the atmosphere of W1906+40 for two years. The L-dwarf had initially been discovered by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer in 2011. Later, Gizis and his team realised that this object happened to be located in the same area of the sky where NASA’s Kepler mission had been staring at stars for years to hunt for planets.

Kepler identifies planets by looking for dips in starlight as planets pass in front of their stars. In this case, astronomers knew observed dips in starlight weren’t coming from planets, but they thought they might be looking at a star spot — which, like our Sun’s “sunspots,” are a result of concentrated magnetic fields. Star spots would also cause dips in starlight as they rotate around the star.

Follow-up observations with Spitzer, which detects infrared light, revealed that the dark patch was not a magnetic star spot but a colossal, cloudy storm with a diameter that could hold three Earths. The storm rotates around the star about every 9 hours. Spitzer’s infrared measurements at two infrared wavelengths probed different layers of the atmosphere and, together with the Kepler visible-light data, helped reveal the presence of the storm.

While this storm looks different when viewed at various wavelengths, astronomers say that if we could somehow travel there in a starship, it would look like a dark mark near the polar top of the star.

The researchers plan to look for other stormy stars and brown dwarfs using Spitzer and Kepler in the future.

“We don’t know if this kind of star storm is unique or common, and we don’t why it persists for so long,” said Gizis.

Gizis is an observational astronomer who is primarily interested in very-low-mass stars and brown dwarfs. These objects can emit photons over most of the electromagnetic spectrum, so many different telescopes are necessary to measure their properties. His current projects make use of X-Ray (NASA’s Chandra Telescope), optical (Kepler/K2, Hubble), near-infrared (2MASS, IRTF) and mid-infrared (Spitzer Space Telescope, WISE, Herschel) telescopes. In 2012 and 2013, I observed at the Kitt Peak 2.1-meter, IRTF 3-meter, MMT 6.5-meter, and Gemini North 8-meter telescopes, all awarded through national competition.