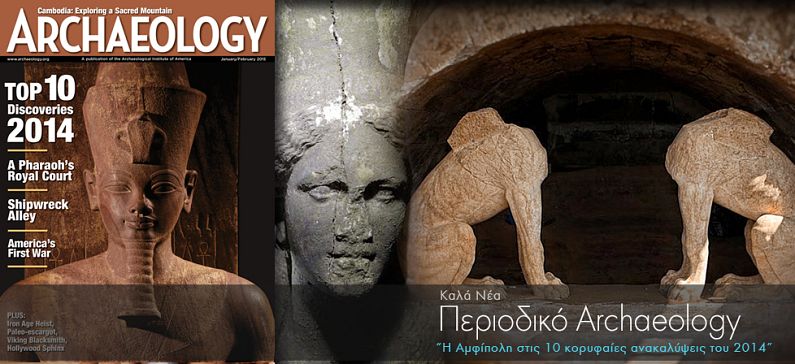

Amphipolis among the top 10 discoveries of 2014

Archaeology Magazine published the Top 10 of discoveries for 2014. The massive and impressive Amphipolis tomb is on number 4 of the list. ARCHAEOLOGY’s editors reveal the year’s most compelling finds and they start their article by mentioning Amphipolis excavation and its impact:

«Ever since the discovery of the largest known Greek tomb was announced in August, archaeology buffs around the world have been eagerly awaiting each successive bit of news from the site. The Amphipolis tomb, which dates to the time of Alexander the Great, is a prime example of how archaeology can captivate the public imagination and easily earned a spot on our list of the Top 10 Discoveries of 2014″.

1. Under Stonehenge Wiltshire, England

As if Stonehenge weren’t spectacular enough, an unprecedented digital survey—involving aerial laser scanning, ground-penetrating radar, and other geophysical and remote-sensing technologies—has revealed that the iconic 5,000-year-old standing stones were part of a much broader Neolithic ceremonial landscape. Unveiled at the British Science Festival in September, the research has revealed 17 new monuments and thousands of as-yet-uninterpreted archaeological features, including small shrines, burial mounds, and massive pits, across nearly five square miles of the Salisbury Plain.

2. Seaton Down Hoard Devon, England

This giant hoard of 22,000 Roman coins discovered in southwest England was most likely buried in the A.D. 340s.A metal detectorist in southwest England has discovered one of the largest Roman coin hoards ever found. The Seaton Down Hoard consists of 22,000 coins, dating from the A.D. 260s through the 340s. According to Vincent Drost, a British Museum numismatist researching the coins, the hoard may represent an individual’s private savings, a commercial transaction, or a soldier’s wages.

3. Buddhism, in the Beginning Lumbini, Nepal

A dig at an active Buddhist shrine in Nepal has uncovered a timber structure dating to around the sixth century B.C. that researchers believe is the world’s oldest known Buddhist shrine. Under the remains of Mauryan temples at Lumbini (themselves topped by a succession of others), archaeologists uncovered evidence of an earlier timber structure upon which all the later temples were based. It dates to around the sixth century B.C., and the researchers, led by Robin Coningham of the University of Durham, believe this makes it the oldest Buddhist shrine in the world.

4. Greece’s Biggest Tomb Amphipolis, Greece

The entranceway to the massive Amphipolis tomb is flanked by two exceptionally well-carved stone sphinxes sitting atop a doorway, much of which would have been brightly painted. Four decades ago, after excavating hundreds of burials in the ancient Greek city of Amphipolis, about 60 miles north of Thessaloniki, Dimitris Lazaridis turned his attention to an enormous mound called the Hill of Kasta, which he believed contained a tomb or funerary monument of tremendous importance. Lazaridis’ work soon took him elsewhere, and archaeologists didn’t return to Kasta until 2012, when they began to expose the 1,500 feet of marble and limestone walls encircling the mound. This past summer the team found the entrance to the extraordinary monument Lazaridis suspected was there from the start. The tomb dates to the last quarter of the fourth century B.C., when Amphipolis was an important city under Greece’s Macedonian rulers.

5. Decoding Neanderthal Genetics Jerusalem, Israel

The secret to differences between modern humans and Neanderthals appears to have as much to do with which genes are switched on and which are switched off as it does with differences in the raw genetic code. Now, researchers from Hebrew University in Jerusalem and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, where the original sequencing took place, have found an ingenious way to investigate Neanderthal epigenetics. Their findings have provided tantalizing clues to how the bodies and brains of modern humans have evolved since splitting from Neanderthals several hundred thousand years ago. The usual methods for determining whether genes are active or inactive are highly destructive and cannot be used on scarce Neanderthal genetic material. Instead, the researchers managed to detect telltale epigenetic signs in the Neanderthal genome based on the insight that certain portions of ancient DNA tend to be misread in a distinctive way by DNA sequencers.

6. Canada Finds Erebus Victoria Strait, Canada

A ship that set out from England in 1845 in search of the Northwest Passage has finally been found in the Canadian Arctic after a decades-long effort.

Rare is the archaeological discovery that gets announced by a head of state. But the discovery of a shipwreck in frigid Arctic waters got just that treatment in September from Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper. “I am delighted to announce that this year’s Victoria Strait Expedition has solved one of Canada’s greatest mysteries,” Harper’s statement reads, “with the discovery of one of the two ships belonging to the Franklin Expedition lost in 1846.”

7. Sunken Byzantine Basilica Lake Iznik, Turkey

The remains of a basilica dating to the fifth century lurked unnoticed under the waters of Lake Iznik just off the shore of the ancient city of Nicaea until they were spotted during an aerial survey. Only 100 miles from Istanbul, the ancient city of Nicaea, on the shores of Turkey’s Lake Iznik, is not remote or unknown. So archaeologist Mustafa Sahin was in for a shock when a routine aerial survey of the lake revealed traces of a fifth-century basilica. “I did not believe my eyes when I saw it under the helicopter,” says Sahin. “I thought to myself, ‘How did nobody notice these ruins before?’” The site is now slated to become an underwater archaeological museum.

8. Bluetooth’s Fortress Køge, Denmark

A newly discovered Viking fortress may have belonged to Harald “Bluetooth” Gormsson, the first king of Denmark.In a field southwest of Copenhagen, beneath a barely perceptible rise, lies what’s left of a fortress that may have been built by Harald “Bluetooth” Gormsson, the tenth-century Viking warrior who became the first king of Denmark. This is the first such fortress to be found in the country in 60 years. Archaeologists used remote-sensing surveys to identify the 475-foot-wide circular structure as well as buildings and pits in and around it. They also excavated two of the fort’s gates and found burned timbers in both, which could suggest that the fortress had been attacked. It is also possible that it was burned when it was no longer needed. There are four other known Viking fortresses in Denmark, all dating to around A.D. 981, during the reign of Bluetooth, and they all have the same layout. This one is providing a new opportunity to learn about the reign of the king who Christianized Denmark and implemented a national government. “It was an amazing time,” says Nanna Holm of the Danish Castle Center. “It is when we became who we are today.”

9. Mummification Before the Pharaohs York, England

Linen used to wrap the dead in Egypt more than 6,000 years ago was permeated with a mixture of substances very similar to that used when the art of mummification was at its height 3,000 years later. Analysis of funerary wrappings that have been stored in Britain’s Bolton Museum since the 1930s has established that Egyptians cooked up recipes to mummify the dead as early as 4300 B.C.—1,500 years earlier than previously thought. The linen wrappings came from cemeteries in the Badari region of Upper Egypt and date to well before the beginning of rule by pharaohs.

10. Naia—the 13,000-Year-Old Native American Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

In 2007, divers found in a 150-foot-deep water-filled trench known as Hoyo Negro (“black hole”) in an underwater cave system in Mexico’s Yucatán, the nearly intact skeleton of a 15- to 16-year-old girl they called Naia (for the Greek water nymph). This year, scientists announced what Naia’s remains revealed. Multiple methods used to date her teeth and bones suggests that she lived between 12,000 and 13,000 years ago, making her one of the earliest humans ever found in the Americas. Analysis of her mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mother to child, show that she had a constellation of genes that is common among modern Native Americans. Her skull construction is also similar to that of Kennewick Man.