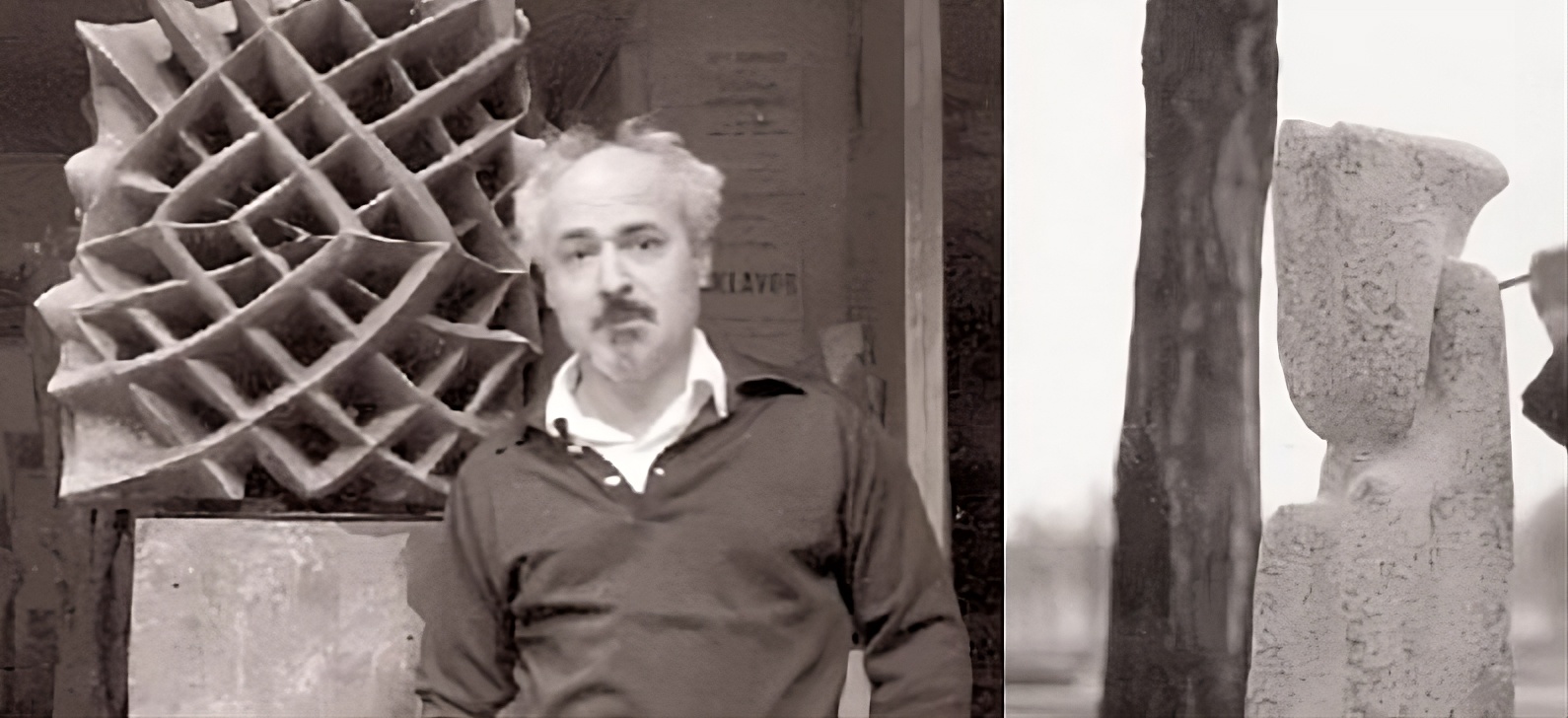

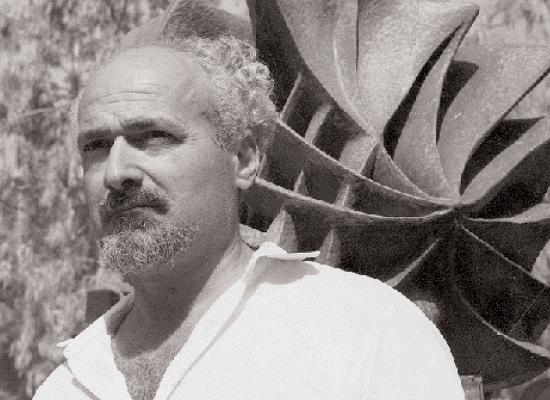

Gerasimos Sklavos was born on September 10, 1927, in Domata, Kefalonia, the fourth of eight children in a farming family. His father envisioned him as a sailor, while he himself dreamed of becoming a pilot. In 1948, he was rejected by the Hellenic Air Force Academy due to an eye condition, a turning point that led him to sculpture. As a child, he had already experimented by shaping female figures out of sand on Kefalonia’s beaches and creating ephemeral snow sculptures during his military service. “I am Greek and feel deeply connected to my homeland. Here I first realized the urgent need to become a sculptor,” he once wrote.

Studies and Early Recognition

In 1950, Sklavos entered the Athens School of Fine Arts, studying under Michalis Tombros until 1956. Soon after, thanks to an IKY scholarship, he continued his studies in Paris until 1960. There, he became closely associated with influential art figures such as the Greek-French critic and collector Christian Zervos and patron Ali de Rothschild, who even provided him with an atelier in Levallois-Perret.

His first major recognition came in 1961, when he won the First Prize at the Biennale of Young Artists in Paris. That same year, Zervos organized his first solo exhibition at the historic Cahiers d’Art gallery. From then until his premature death, Sklavos participated in numerous exhibitions worldwide, drawing praise from the art world, with some calling him “the greatest sculptor of the 20th century after Giacometti.”

Sculpture of Light and the Art of “Tele-Sculpture”

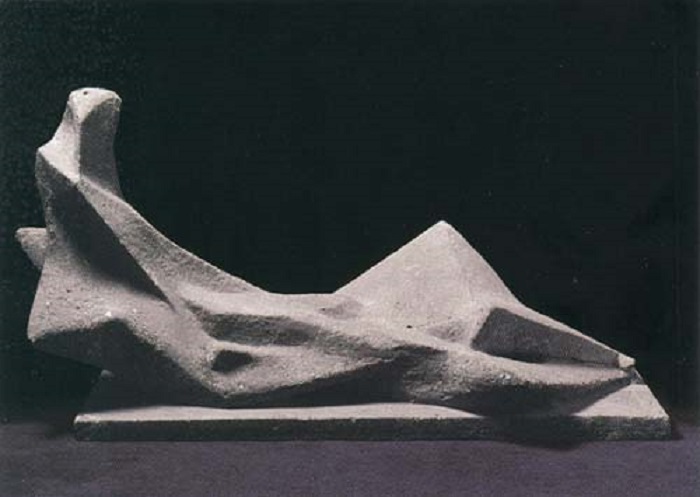

Sklavos initially worked with figurative representation, exploring a blend of psychographic and abstract expression of the human form. By 1959, he fully embraced abstraction, drawing inspiration from nature and the elements. He worked primarily with hard materials such as granite, marble, and porphyry. In 1960, he invented a groundbreaking technique: a machine that projected oxygen and acetylene, enabling him to carve even the hardest stones. He called this method tele-sculpture.

On a slab of Pentelic marble, he engraved his artistic manifesto, with light at its core: “Light is the beginning of the creation of the universe – Light, movement, speed – interplanetary light – infinite dimensions.” For him, light symbolized life, soul, and the very essence of artistic creation.

The “Delphic Light” and the Mysticism of His Work

Among his most celebrated works is Delphic Light (1965–1966), carved from Pentelic marble and placed in the gardens of the Amalia Hotel in Delphi. “In Delphi my soul was set aflame. The scepters belong to light,” he wrote, highlighting the spiritual and metaphysical depth of his art.

In the same period, his works were presented in Athens, and the National Gallery of Greece acquired his marble sculpture La Passante. In 1966, he held his last solo exhibition at the Hilton Athens.

A Premature and Tragic Death

On January 28, 1967, Sklavos’s life came to a tragic end. At his studio in Athens, during a power outage, he stumbled in the dark over one of his own massive sculptures, The Friend Who Never Stayed. The piece shifted and fatally crushed him, bringing an abrupt close to his brilliant career.

Just hours earlier, he had completed another masterpiece, The Last Vision, carved in Pentelic marble, where he inscribed the haunting words: “And if it remains in the darkness, write with the eyes of the soul.”

Despite his short life, Gerasimos Sklavos left an indelible mark on modern sculpture. Known as the “sculptor of great volumes,” he combined Greek tradition with avant-garde artistic expression, creating works that remain timeless. For Sklavos, sculpture was never just about material and form — it was light, motion, and soul.